An overdue appreciation of ST Gill, Australia’s first painter of modern life

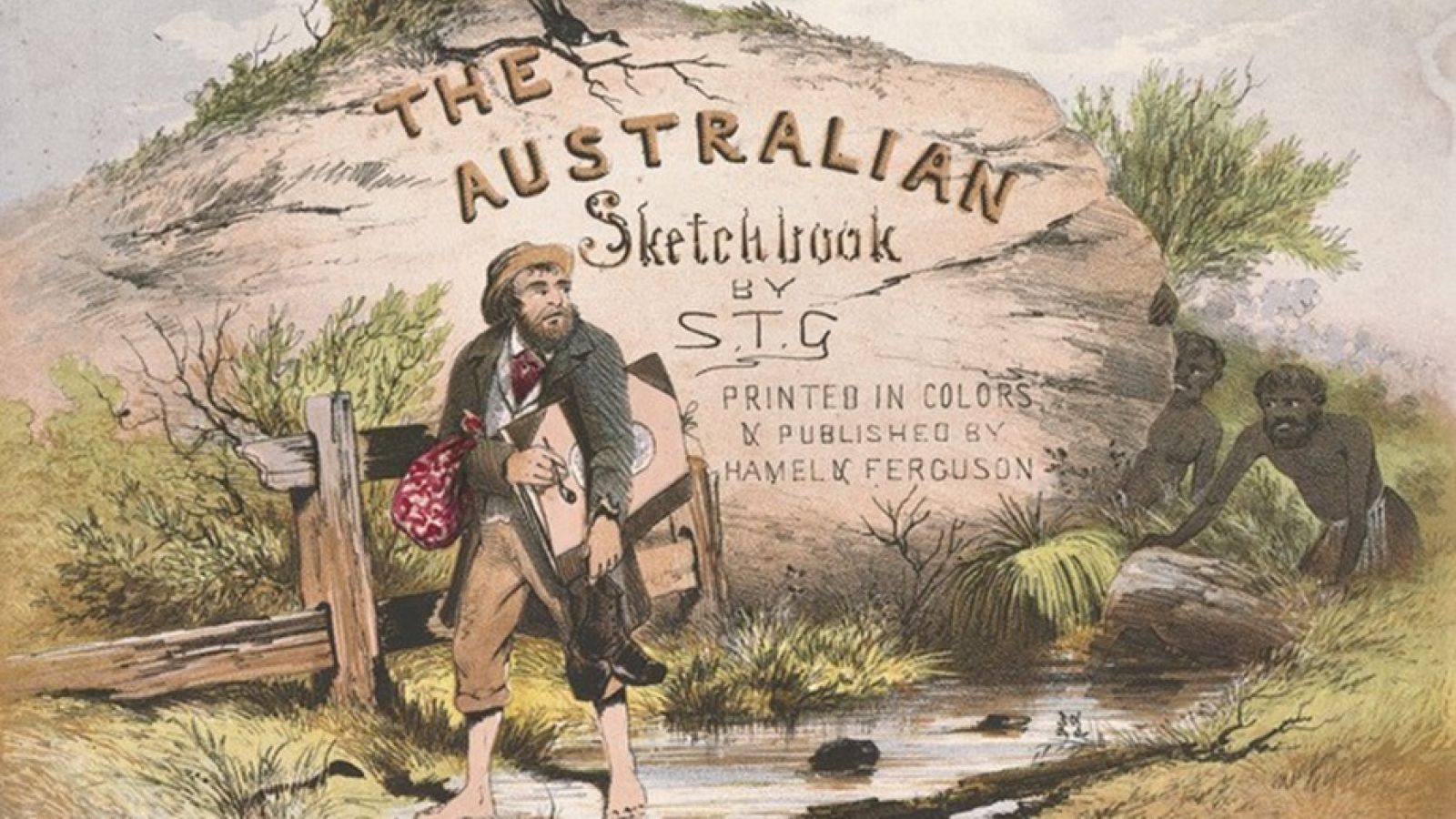

Title Page of the Australian Sketchbook 1864-65 chromolithograph. State Library of Victoria.

By Sasha Grishin, Adjunct Professor of Art History, School of Literature Languages & Linguistics

ST Gill may be the quintessential Australian colonial artist, known to anyone who has been educated in Australia and seen textbooks on Australian history full of Gill illustrations of the gold rushes, yet he has never been the subject of a comprehensive retrospective exhibition. At least, not until now.

The fault, at least in part, is mine. About 25 years ago I embarked on a major ST Gill project to compile a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of his work leading to the publication of a substantial book and a large curated retrospective exhibition.

It took longer than shorter and now, at last, the book is out and the exhibition opens to the public on July 17 at the State Library Victoria.

Independent satellite Gill exhibitions are opening simultaneously at the regional galleries in the centre of Victoria’s “Gill country” at Ballarat, Bendigo, Castlemaine and Geelong, while at the University of Melbourne, there is an international Gill conference plus an in-focus exhibition on Gill’s studies for the iconic Doing the Block, Great Collins Street (1880).

STG, as he was universally known, may have had to wait 135 years since his death to be comprehensively celebrated, but Victoria is now honouring him in style and the show will travel to the National Library of Australia in 2016.

So, who was Gill and why was he lionised in the 1850s, neglected later in life and subsequently relegated to art historical purgatory?

He was born in Somerset in England in 1818, where he received his early training in Devonport, Plymouth and London. The Gill family migrated to South Australia, when he was 21, arriving in the newly established colony just before Christmas in 1839.

For the next 41 years Gill, in Australia, worked at a frenetic pace, initially spending 12 years in South Australia, then four years in Victoria, much of this time on the goldfields, then seven or eight years in Sydney and then the final 16 years of his life based predominantly in Melbourne, where he died in relative poverty in 1880.

Like his contemporaries George Cruikshank and Honoré Daumier , Gill’s output was prodigious, with about 3,000 items by his hand catalogued thus far. That was in keeping with the rate of production by his contemporaries working within the tradition of democratic multiples.

Gill produced watercolours, pen and brush wash drawings, pencil drawings and sketches, lithographs, other forms of prints, and possibly daguerreotypes. He may have experimented with oils, but few or no oil paintings are extant which are indisputably by his hand.

Gill may have arrived in Australia with all of the baggage of a liberal-minded Englishman, whose father had been a Baptist minister and subsequently dissented and joined the Plymouth Brethren, but within a couple of years in the colony he was questioning the values inherited from the old country.

There is evidence in his art that he spent a considerable amount of time with Indigenous people and came to respect the way they lived within their environment. Subsequently in his work he bore witness to how Indigenous Australians had become dispossessed and exploited in their own land.

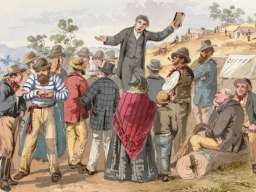

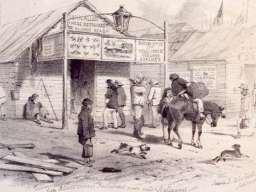

He gave the Victorian goldfields a human face and, unlike many of the other artists who showed successful diggers posed with their discovered huge nuggets, Gill more than anything else showed the experience of “being there”. When xenophobic politicians whipped up hysteria against the Chinese boat people, accusing them of stealing our gold and jobs, Gill in his art condemned racism and celebrated the hardworking Chinese miners and depicted the first Chinese takeaway restaurant in Ballarat.

Gill showed women on the goldfields, something other artists tended to shy away from. He depicted them rocking the cradle, extracting the gold, looking after the family as well as running the notorious sly grog tents.

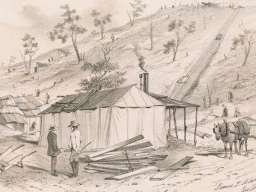

Gill also showed the dark side of the gold rushes with the creation of an environmental wasteland stripped of flora and fauna with choked waterways.

Between August and October 1852 he produced 48 small black and white lithographs titled Sketches of the Victoria Diggings and Diggers As They Are, which were widely imitated and became some of the most famous works from colonial Australia.

In Gill’s art of the early 1850s, a new human species was given visual form, that of the Aussie digger: tough, resilient, resourceful, possessing a dry humour, one who was true to his mates, but intolerant of all forms of authority, humbug and institutionalised religion.

The visual typologies Gill developed were subsequently built upon by the artists of The Bulletin, including Phil May, and later hijacked and mythologised by the nationalist propagandists of the Great War.

It was between 1852 and 1856 that Gill reached his greatest popular acclaim, he was lionised as the Australian Cruikshank and he was mercilessly plagiarised in Europe, at times by artists of major standing, including Gustave Doré.

In Adelaide Gill worked primarily for a British audience and the illustrious James Allen took Gill’s paintings with him to England to employ as visual propaganda to accompany his lectures designed to encourage migration to the colony of South Australia. But by the time Gill was working in Victoria, his primary audience had become local and his lithographs and letterhead papers were sent abroad by those living in the Australian colonies as testimony as to what was happening in Australia.

As an artist, Gill became more accomplished as he grew older and some of the finest work dates from the final decade of his life. It was also at this time that he was marching to a different drummer to the one who commanded the attention of the small but growing Australian art audience which hankered for glowing romantic oil paintings or Barbizon-style picturesque landscapes.

Gill was a democratic socialist in his orientation, one who was increasingly critical of authority, high society and the official church. In his later years he was surrounded by a shrinking band of supporters, died in poverty and was largely forgotten.

Although the myth that he died as a hopeless alcoholic who could not hold a paintbrush has been discredited, he did suffer from neglect in his later years. The real cause of his death, as we now know from the post-mortem, was an aortic aneurysm, which was generally associated with high blood pressure and a family history of heart problems.

The claim which I make in this exhibition, as curator, is that Gill was one of the most important colonial artists of Australia. What he sought to achieve in his art was quite different from that of most of his contemporaries, including Eugene von Guérard, Nicholas Chevalier, William Strutt and Louis Buvelot.

He interrogated Australian society and its values, questioned our attitudes to our environment and created a visual tradition on which many other artists have built. In many ways he is Australia’s first painter of modern life.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.